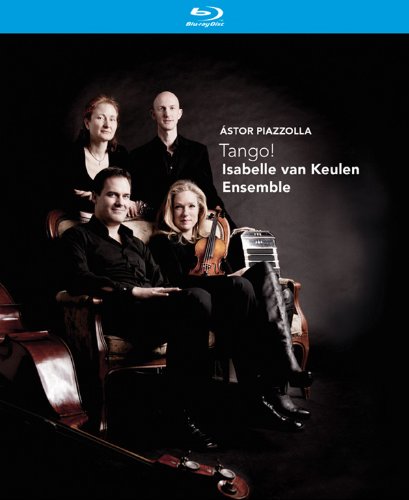

💓 Tango! concert. Ástor Piazzolla tango nuevo music performed 2013 by the Isabelle van Keulen Ensemble at the MotorMusic Studios in Mechelen, Belgium. The Isabelle van Keulen Ensemble is a chamber music group formed primarily to play Piazzolla compositions; it consists of van Keulen on violin, Christian Gerber on bandoneón, Ulrike Payer on piano, and Rüdiger Ludwig on double bass. Music director was Felicia Van Boxstael and the recording producer was Steven Maes for Serendipitous. The executive producers were Anne de Jong and Marcel van den Broek. Project coordinators were Jolien Plat and Inge De Pauw. Released 2013, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A+

[Special note: as a PS, we have added interesting material about the history of tango nuevo and this recording written by Rüdiger Ludwig, the bass player on this disc. This material was in the CD booklet but is not in the Blu-ray package.]

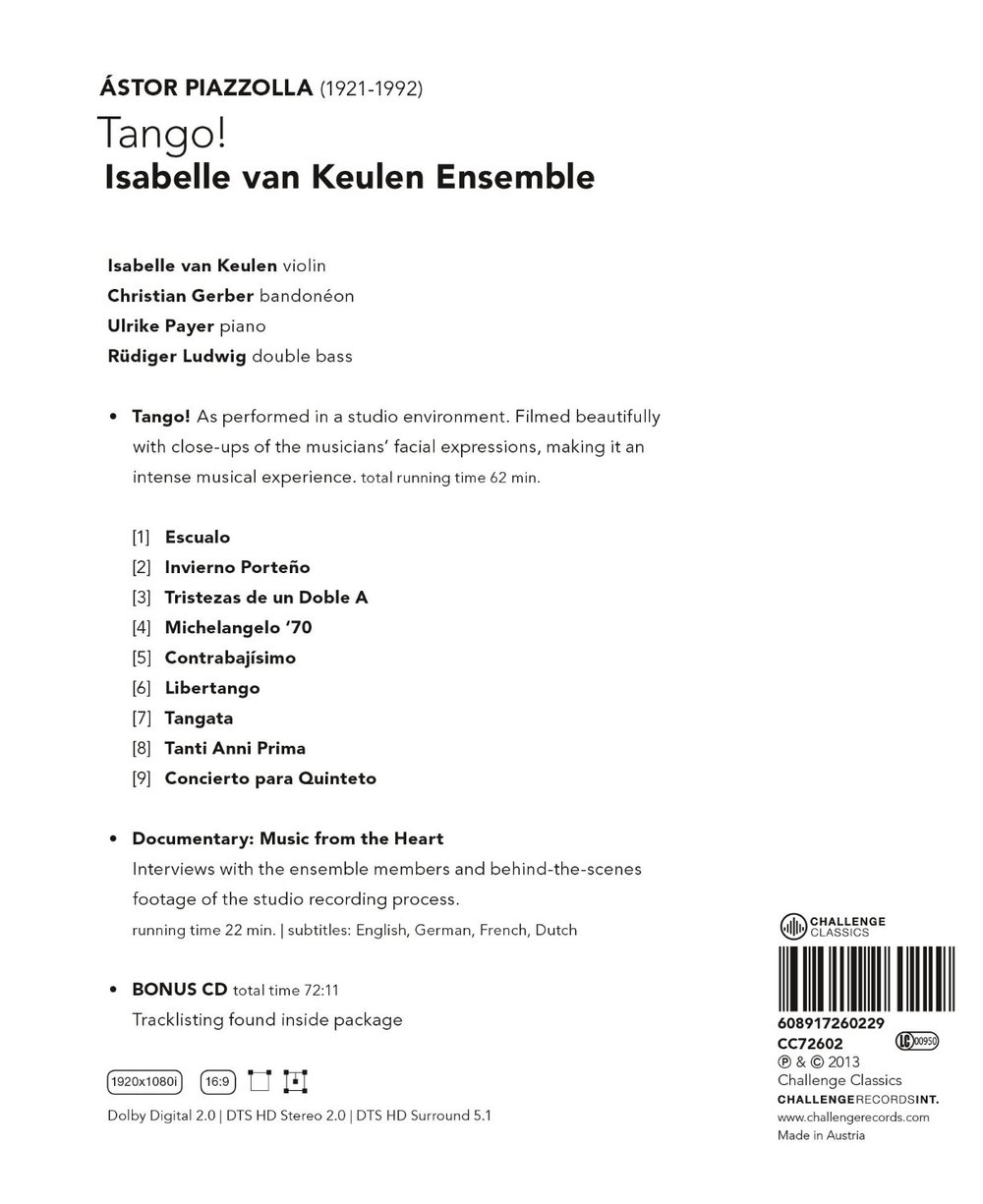

Here's the Blu-ray program (62 minutes of Piazzolla compositions and 22 minutes of documentary). The songs are listed by track numbers on the Blu-ray (there are more tracks on the bonus CD):

Escualo (Shark)

Invierno Porteño (Buenes Aires in Winter)

Tristezas de un doble A (Sorrows of a Double A. This is in honor of Alfred Arnold, who made Piazzolla's favorite bandoneóns)

Michelangelo '70 (The name of a nightclub in Buenes Aires)

Contrabajísimo (Written for Piazzolla's favorite bass player. Probably untranslatable; I like Boss of the Bass)

Libertango (A popular name for Piazzolla's formal style of writing tangos) (Arranged by Christian Gerber)

Tangata (Perhaps just a play on the word "tango")

Tanti anni prima (Means "many years ago" in Italian; is often called the Piazzolla Ave Maria)

Concierto para Quinteto (Concerto for Quintet. For this group, it's a Concerto for Quartet)

Music from the Heart Documentary

I swear I don't have stock in Challenge Records. I've only played two of their titles, this Tango! and their Winterreise. But I can make a case that both of these are better than any other classical music record ever made by anyone outside of the Japanese home market. Here's the case: both records have more than an hour of classical music from leading international musicians + a worthwhile back-stage bonus + decent HD video + sound recorded at 96kHz/24bit or higher. Nobody else in the West has put this together even once, so Challenge is now in class by themselves. (RCO Live tried to make a excellent box set of all the Mahler symphonies played by the Concertgebouw Orchestra; but that project got swallowed up in a sinkhole of bad video and mistakes in disc authorship.)

Can tangos be classical music? Much of classical music can be traced to dances. The dances died centuries ago, but the music lives on. Ástor Piazzolla started playing in dance halls. But he was a universal musical talent who acquired traditional classical music training and composed many kinds of music. Eventually he merged dance tangos into mainstream classical music in the form of tango nuevo or libertango. The pieces you hear on this record are tango nuevo. They can only be played by master musicians, are intended for serious listening, and have been accepted as a genre of modern classical music. (Piazzolla typically performed the music presented here with a quintet that included an electric guitar. Per Rüdiger Ludwig, van Keuren parceled out the guitar part on Tango! to the piano, violin, and bandoneón. Piazzolla was constantly experimenting with everything, so we can assume he would approve.)

Here's the set up at the recording studio. The idea was to create a “smoky,” slightly soft indie-film look that might remind one of a dance hall. From left to right are Rüdiger on bass, Ulrike on piano, Christian with his Bandoneón, and Isabelle:

The setup makes it hard to get video of the ladies. Here's a better shot of Isabelle who plays and conducts standing up (in heels!):

The musicians seem to have enough room, but the recording space quickly gets crowded and a bit chaotic with the addition of camera crews. This results in slightly nervous, unpredictable, improvised-on-the-fly photography. With this in mind, don't be upset with focus and composure errors that pop up—the video style matches the moody, dramatic nature of the music. Finally, I ran the numbers on the video pace. The average clip last lasts a bit over 11 seconds, which is about the same as most of the better symphony videos we have.

The black and white shots are from the documentary. The color shots are of the concert:

To work in this environment, it helps to be able to converse in Spanish, Dutch, German, French, and English simultaneously:

A Dutch girl gets to play tangos because she grew up enchanted by them. She became a famous musician and university professor of violin and viola. Piazzolla gave her the tango nuevo movement with written scores. Isn't this the best possible definition now of the term “classical music?”

But there is still Tango lore that newbies have to learn somehow. Ulrike is thrilled:

And Christian explains how when he was starting in music, there were only 2 people in Europe who had mastered the bandoneón. He found them out, and they gave him classes. In the old days, the bandoneón players sat in chairs. Piazzolla invented the technique of standing and making a saddle for the instrument with the upper leg as you see here:

Here's a better shot of Ulrike:

We haven't said much about Rüdiger. In this music, he gets the parts of second violin, viola, and cello as well as bass. His spectacular number is Contrabajísimo, the only bass solo I can think of now that doesn't seem to be to be a stunt. They say Contrabajísimo was the only music played at Piazzolla's funeral:

I should mention that all the musicians double as percussionists to make tango sound effects. Here Isabelle is using the gold band on her left-hand ring finger to whack the scroll of her violin for a sound that startles:

And Ulrike mounts a surprise attack on some treble strings that have dropped their guard:

So what is this music like? It's characterized by intense rhythm, violent swings in mode and method, and what Isabelle calls "naked" rawness. Every bar demands your complete attention. But there's little cheerful or elating about it. The overwhelming emotion of most of the numbers is sadness, especially when the mournful bandoneón is doing anything other than rhythm. When I say sad, I mean sadder than all the trains and planes you ever heard at night. I mean not just broken hearts, but evicted families salvaging their clothes in the rain, sons missing in the civil war, a mother who sells herself to buy medicine for a child—that kind of sad.

But in some of the numbers there is also relief—the unsoundable sweetness of requited love. Long ago I experienced this in my life's favorite musical moment. A girl and and a boy from the conservatory were playing Mozart violin and viola duets in a coffee shop for tips. I was sitting 6 feet away. I suddenly realized they weren't playing for us anymore. They were making love. When they finished, my coffee, untouched, was cold. The girl looked at me. She seemed happy because she saw that I understood how she felt.

Now back to Tango! and "Tanti Anni Prima." This is a duet for violin and bass with piano in the background. When I saw Isabelle and Rüdiger doing this, I thought of the coffee shop: these guys aren't just trusted colleagues—this violin and this bass are lovers! Maybe you can get some idea about this from these shots:

Even Ulrike was getting in the mood:

Turns out I was right! From the documentary, we learn a that the violin and bass are "partners":

It's been such a pleasure to learn more about the tango. And I'm grateful for getting a tiny glimpse into the lives of these beautiful people:

OR

[PS: German first and then in English.]

Dekonstruktion einer Volksmusik---Astor Piazzolla und der Tango Nuevo by Rüdiger Ludwig

Als Verruckter "mit seltsamen Ideen und sinnlosen Modernismen" galt Astor Piazzolla zu Beginn seiner Karriere in seiner argentinischen Heimat, angefeindet von Traditionalisten und Puristen, die das Nationalheiligtum Tango in Gefahr sahen.

Indem er den Tango mit Elementen und Spieltechniken der klassischen Moderne und des Jazz konfrontierte und damit scheinbar gegensätzliche musikalische Richtungen verband, schuf er eine neue, eigene Art des Tango, nicht wirklich tanzbar, sondern konzentriertes Hören erfordernd. Piazzollas Tango Nuevo verliert dennoch nie das Romantische und die Leidenschaft, die Dramatik, Erotik und Heftigkeit des traditionellen Tangos.

In 1921 in der argentinischen Stadt Mar del Plata geboren verschlug es Astor Piazzolla drei Jahre später gemeinsam mit seinen italienischen Eltern nach New York. Sein Vater eröffnete in Greenwich Village einen Friseursalon und bekämpfte sein Heimweh mit dem pausenlosen Abspielen von Tango-Schallplatten. Nach Erkennen der Musikalität des Sohnes erhielt Astor Klavierunterricht und erlernte daneben auch das Bandonéonspiel, mehr dem Vater und seiner Tangomanie zuliebe, denn seine eigene erste musikalische Wahl war eigentlich der Jazz-und Johann Sebastian Bach, nicht der Tango: "Mein Vater hörte ständig Tango und dachte wehmütig an Buenos Aires zurück, an seine Familie, seine Freunde – seine Traurigkeit, sein Ärger und immer nur Tango, Tango".

Im Jahre 1936 jedoch, nachdem die Familie nach Buenos Aires zurückgekehrt war, erfuhr Piazzolla ein Schlüsselerlebnis. Bei einem Konzert des Tango-Ensembles von Elvino Vardaro erlebte er eine für ihn neuartige Tango-Interpretation, die nun seine Leidenschaft entfachte. Er intensivierte und perfektionierte daraufhin sein Bandoneonspiel und wurde 1939 Mitglied im Orchester von Anibal Troilo, dort begann auch seine Karriere als Arrangeur und Komponist. Ab 1940 nahm Piazzolla Kompositionsunterricht bei Alberto Ginastera (1916–1983), einem der wichtigsten lateinamerikanischen Komponisten des 20. Jahrhunderts. Er schrieb Orchester- und Kammermusik und vernachlässigte das Bandoneon, und obwohl er auch Tangos komponierte, trat er mit diesen nicht an die Öffentlichkeit. Er wollte als ernstzunehmender Komponist wahrgenommen werden und glaubte, dass ihm dies als Tangomusiker nicht gelingen konnte. Der Tango war in dieser Zeit in den Bordellen und Kabaretts zu Hause und genoss nicht den besten Ruf, vor allem die Oberschicht verachtete die Musik.

Mit einem Stipendium ging Piazzolla schließlich nach Europa, wurde Schüler von Nadia Boulanger in Paris, Lehrerin solch musikalischer Grössen wie Aaron Copland und Philip Glass, und wollte seine Kompositionstechnik perfektionieren, seine Wurzeln in der Tangomusik jedoch verschweigend: “In Wahrheit schämte ich mich, ihr zu sagen, daß ich Tangomusiker war, daß ich in Bordellen und Kabaretts von Buenos Aires gearbeitet hatte. Tangomusiker war ein schmutziges Word im Argentinien meiner Jugend. Es war die Unterwelt." Nadia Boulanger fand in Piazzollas Musik Einflüsse von Ravel, Strawinsky, Bartók und Hindemith vor und die Kompositionen wiesen zweifellos Qualität auf. Was sie jedoch vermißte, war eine individueller Stil des Komponisten Piazzolla, seine Seele. Schließlich bat sie ihn, einen Tango auf dem Klavier zu spielen: “Du Idiot! Merkst Du nicht, daß dies der echte Piazzolla ist, nicht jener andere? Du kannst die gesamte andere Musik fortschmeißen!” Sie bestärkte ihn, das Bandoneonspiel und den Tango wieder aufzunehmen: “Dein Tango ist die neue Musik, und sie ist ehrlich.”.

1955 kehrte Piazzolla nach Argentinien zurück. Er gründete das Octeto Buenos Aires: zwei Bandoneons, zwei Violinen, ein Kontrabass, Cello, Klavier und eine elektrische Gitarre. Mit diesem Ensemble begann die Neuinterpretation des Tangos: Der Tango Nuevo. Der Tango wurde wie nie zuvor seziert, kunstvoll mit unerhörten Harmonien und Rhythmen angereichert und zu etwas Neuem zusammengesetzt. Dabei blieb der traditionelle Tango stets spürbar mit seinen synkopischen Rhythmen, scharfen Betonungen und vor allem dem melancholischen Melos.

1960 gründete er ein weiteres Ensemble, das Quinteto Tango Nuevo, ein Ensemble aus Violine, Gitarre, Klavier, Kontrabass und Bandoneon. Anfänglich stießen seine Werke auf Kritik und Ablehnung, da sie sich vom ursprünglichen Tango stark unterschieden und es manche Puristen störte, dass mit Piazzolla der Tango von seinem angestammten Ort, dem Tanzparkett, in den Konzertsaal verlegt wurde. Die Anfeindungen gingen so weit, dass Piazzolla und seine Familie sich in Buenos Aires mitunter kaum auf die Straße wagen konnten. Doch er arbeitete weiter und komponierte, konzertierte und erstellte Arrangements seiner Werke für unterschiedliche Besetzungen mit enormer Produktivität.

Im Laufe seines Lebens komponierte er über 300 Tangos und Musik für fast 50 Filme und spielte rund 40 Schallplatten ein, arbeitete mit Literaten und bildenden Künstlern zusammen und auch für das Tanztheater Pina Bauschs.

Während der argentinischen Militärdiktatur von 1976 bis 1983 lebte Piazzolla in Italien, kehrte aber immer wieder nach Argentinien zurück. Insbesondere die Zeit von 1978-1988 gilt als Höhepunkt seines Schaffens. In dieser Zeit feierte er mit seinem zweiten Quintett, in dem Pablo Ziegler (Klavier), Fernando Suarez Paz (Violine), Horacio Malvicino (Gitarre) und Hector Console (Kontrabass) mitwirkten, auch in der Heimat endlich große Erfolge.

Nach dem Ende der Militärdiktatur kehrte er nach Buenos Aires zurück, wo man Piazzolla 1985, also vier Jahre vor seinem Tod, zum Ehrenbürger der Stadt kürte.

Als er mit 65 Jahren im Jahr 1986 das beeindruckende Spätwerk "Tango Zero Hour" veröffentlicht, gilt der Mann aus Buenos Aires längst als lebende Legende. Im August 1990 erleidet er in Paris einen Schlaganfall, der weiteres Komponieren und Konzertieren unmöglich macht. Piazzolla stirbt zwei Jahre später in seiner Heimatstadt.

Erst spät wurde in seinem Heimatland erkannt, welch Genie Astor Piazzolla besaß. Die gleichzeitige Komplexität und emotionale Ausdruckskraft seiner Werke begeistert seitdem Musiker aller Stilrichtungen, so auch klassisch geprägte, wie auf der hier vorliegenden Einspielung.

Escualo,"Hai", ein Titel aus dem Jahre 1979, setzt die Violine in den Vordergrund. Verbunden mit höchsten virtuosen Ansprüchen zieht der treibende Rhytmus und der elegische Mittelteil schlagartig in den Bann.

Verano ("Sommer") Porteño und Invierno ("Winter") Porteño sind 1965 und 1970 entstandene Stücke aus den "Estaciones Porteños", den vier Jahreszeiten von Buenos Aires, angelehnt an Vivaldis Jahreszeiten. Ursprünglich waren diese jedoch als einzelne Titel und weniger als Suite gedacht.

Tristeza de un doble A ("Die Traurigkeit eines Doppel A") ist eine Hommage an das Bandoneon-das ursprünglich aus Deutschland stammende, von Heinrich Band erfundene Bandoneon gelangte vor allem in Argentinien zu großer Popularität und wurde das charakteristische Instrument des Tango. Das "Doppel A" steht für ein "richtiges" Bandoneon aus der Fabrikation von Alfred Arnold ("AA") aus Carlsfeld.

Während Michelangelo 70 die hitzige Atmosphäre eines gleichnamigen Tangoclubs in Buenos Aires heraufbeschwört, spricht der nächste Titel Contrabajisimo für sich: nach einer ausgedehnten Solo-Kadenz des Kontrabasses entwickelt sich ein komplexes, von verschiedenen melancholischen Soli aller Instrumente durchzogenes stringent nach vorne treibendes Werk, dass mit großer Geste endet.

Libertango aus dem Jahre 1974 ist eines der bekanntesten Werke aus der Feder von Astor Piazzollas-der Name symbolisiert den Aufbruch vom klassischen Tango zum Tango Nuevo in der Verbindung der Worte Libertad ("Freiheit") und Tango.

Die Titel Oblivion und Tanti Anni Prima ("Viele Jahre davor", auch bekannt als "Ave Maria") repräsentieren Astor Piazzolla als Komponist von Filmmusik-sie entstanden für den Film "Enrico IV" mit Claudia Cardinale von Marco Bellocchio und gehören zu den am meisten gespielten und arrangierten Stücke des argentinischen Meisters.

Tangata, neben Soledad und Fugata Teil einer für den argentinischen Choreograph Oscar Araiz geschriebenen Suite, und auch das Concierto para Quinteto sind beides gross angelegte Werke von höchster Komplexität und Kraft. Sie zeigen noch einmal den Einfallsreichtum, die kompositorische Virtuosität, Innovativität und nicht zuletzt herzergreifende Schönheit des Tango Nuevo und dem Werk Astor Piazzollas-Musik, die Kopf, Herz und Seele verbindet, ungeachtet der Nationalität.

Deconstruction of a folk music – Astor Piazzolla and Tango Nuevo by Rüdiger Ludwig

Astor Piazzolla was seen as "a nutcase with strange ideas and pointless modernisms" at the beginning of his career in his home country, Argentina. Traditionalists and purists resisted the way he combined folk tango with seemingly incompatible techniques used in jazz and modern classical music to create a new music that was not good for dancing, but only for listening. They didn't understand, however, that Piazzolla’s Tango Nuevo never lost the romance, passion, drama, eroticism, and intensity of traditional tango.

Three years after his birth in 1921 in the city of Mar del Plata, Argentina, Astor Piazzolla moved with his Italian parents to New York. His father opened a barber shop in Greenwich Village and fought against his homesickness by listening to tango recordings, day and night. His parents recognized Astor’s musical talent, and he received piano and bandoneon lessons. Astor played the bandoneon more for his father than himself---Astor’s passion was for jazz ---and Johann Sebastian Bach---not tango. "My father listens to tango all the time and is thinking of Buenos Aires, his family, his friends, his melancholy, his anger. Tango, always Tango."

Still, in 1936, after his family had returned to Buenos Aires, Astor had a life-changing experience. At a tango concert by Elvino Vardaro and his band, Astor heard a new way of playing tango. This kindled a passion in him to master the bandoneon. In 1939 he became a member of Anibal Triolo’s tango orchestra; and with Triolo, Piazzolla also began his career as arranger and composer. In 1940 Piazzolla took composition lessons with Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983), one of the most influentual Latin American composers of the 20th century.

He composed orchestra and chamber music. Although he still practiced, he refrained form appearing in public with the bandoneon. He wanted to be known as a important composer, and he believed he could not achieve this playing bandoneon. Tango was mostly played in brothels and cabarets and didn't have the best reputation, especially with the upper crust.

After having received a scholarship, Piazzolla set off to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger, a teacher of composers like Aaron Copland and Philip Glass. He longed to perfect his composition technique and obscured his tango roots: "In fact I was ashamed to tell Boulanger that I was a tango musician, that I played in brothels and cabarets. To be a tango musician was a dirty word in those days. It was the underworld." Boulanger noticed influences of Ravel, Bartok, Strawinsky and Hindemith in Piazzolla’s compositions. But his music lacked an individual style, a soul. At some point she asked him to perform a tango at the piano, and after hearing this she cried out: "You idiot! Don’t you notice that this is the one and only Piazzolla? You can throw all the other stuff away!" She inspired him to take up the bandoneon and tango again: "Your tango is new, and it is honest."

In 1955 Astor Piazzolla returned to Argentina and founded the Octeto Buenos Aires: two bandoneons, two violins, a double bass, a cello, a piano, and an electric guitar. With this ensemble the new genre was born: tango nuevo. The traditional tango was totally dissected, enriched with exciting new harmonies and rhythms, and transformed into something new. But always the traditional tango could be still be detected with its syncopated rythms, sharp accents, and, above all, the strong melancholic expressive line.

In 1960 Piazzolla founded another group, Quinteto Tango Nuevo, existing of violin, guitar, piano, double bass, and bandoneon. Again the music was met with criticism and scepticism because it was changing the scene from the dance floor to the concert hall. For a time, it even reached the point where Piazzolla and his family could hardly dare go onto the streets. In spite of all this he remained enormously productive at composing, performing, and arranging.

In the course of his life he wrote over 300 tangos, music for nearly 50 films, and made around 40 recordings. He collaborated with visual artists, authors, and with Pina Bausch’s Tantztheater.

Between 1976 and 1983 (the time of the military dictatorship) Piazzolla lived in Italy, returning to Argentina regularly. He was especially productive the years 1978-1988. He finally celebrated great success in his home country with the second Quinteto: Pablo Ziegler (piano), Fernando Suarez Paz (violin), Horacio Malvicino (guitar) and Hector Console (double bass). He returned to Buenos Aires in 1985, seven years before his death, where he was then proclaimed Citizen of Honor.

When he finally published "Tango Zero Hour" in 1986 (he was then 65) Piazzolla had long become a living legend. In August 1990 he had a stroke while in Paris and was no longer able to compose or play. Two years later he died in Buenos Aires.

His genius was recognized relatively late. The complexity and emotional power of his compositions have impressed new generations of musicians, including the classically trained ones making this recording.

Escualo, ("Shark"), a title from the year 1979, puts the violin in front. Amidst hair-raising technical difficulties, the listener is captivated by abrupt changes between driving rhythum and a elegiacal central movement.

Verano Porteño ("Summer in Buenos Aires") and Invierno Porteño ("Winter in Buenos Aires") are 1965 and 1970 composed pieces from the "Estaciones Porteños", the seasons of Buenos Aires, based on Vivaldis Four Seasons. Originally they were meant to be single titles and not considered a kind of a suite. [Only Invierno Porteño is on the Blu-ray.]

Tristeza de un Doble A ("The sadness of a Double A") is an homage to the bandoneon. The instrument was invented by Heinrich Band in Germany. It achieved its greatest popularity in Argentina and became the tango’s characteristical instrument. The Double A stands for a "real" bandoneon, made by Alfred Arnold ("AA") in Carlsfeld, Germany.

Michelangelo 70 represents the heat of the identically-named tango club in Buenos Aires. The following title Contrabajisimo speaks for itself: a long double-bass cadenza is followed by a complex section in which all instruments have solos---ending in a grand finale.

Libertango, written in 1974, is probably Piazzolla’s most famous composition. The name combines the words libertad (freedom) and tango and stands for the transformation from tango to tango nuevo.

Both Oblivion and Tanti Anni Prima ("Many years ago", also known as Ave Maria) are titels from film music. They were composed for the Marco Bellocchio movie " Enrico IV" with Claudia Cardinale. These are probably Piazzolla’s most arranged and played pieces.

Both Tangata (part of a suite written for the Argentinian choreographer Oscar Ariaz) and Concierto para Quinteto are songs of great complexity and strenght. Both demonstate again the richness of Piazzolla’s ideas, his vituosity as a composer, and the heartbreaking beauty of tango nuevo---combining heart, body and soul without borders or nationality.